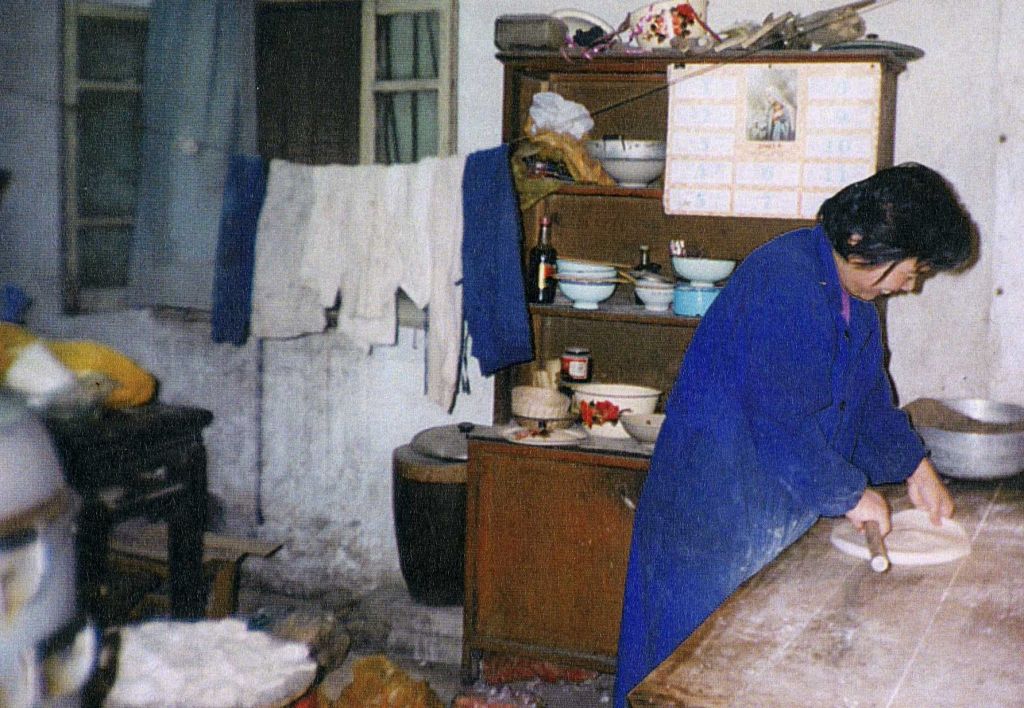

Sacred Heart of Mary sisters prepare food in front of their convent. This photo was taken by Sr. Joyce Meyer during a 2003 trip to China when she was executive director of the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters. (Courtesy of Joyce Meyer.)

A webinar on female religious life China that I attended several months ago continues to fascinate me. The session was sponsored by the International Scholars of the History of Women Religious Association (ISHWRA) at Durham University, England. I’ve long been interested in women religious in China and wanted to share some of what I learned about women who are not often heard from in our Western part of the world.

Michel Chambon, a French theologian and cultural anthropologist at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, where he studies Christianity in the Chinese world, spoke to us on the evolution of female religious life in China. I was able to obtain his original 2019 article “Chinese Catholic Nuns and the Organization of Religious Life in Contemporary China” from the anthropology department of Hanover College in Indiana. It helped fill in the short presentation he made in the hourlong webinar and discussion. I found Chambon’s reflections intriguing, challenging and inspiring.

My personal introduction to sisters in China was in 2003 when I visited as executive director of the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters. At that time, my attention had been on their ministries and I had not given much thought to the development of religious life in China as a whole. However, through our conversations I was inspired by the resilience women religious in China showed in facing the challenges from the 1980s when sisters who had been dispersed in the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution were allowed to come out of the shadows. In private conversations, the sisters shared with me some of their painful navigation of generational issues and different ways of viewing religious life. However, they were not deterred from moving forward, in spite of both internal and external challenges of finance, to re-establish their congregations.

Chambon began his presentation by noting that Catholic nuns who make up female religious life in China first appeared in the 1600s via male Spanish and French missionaries. This timing was similar to that of Catholic female religious life in Vietnam, initiated in that same era. He cited 2015 surveys estimating that about 4,570 women religious lived in the People’s Republic of China at that time, some belonging to the nationally registered or official Catholic Church and others to what has been called the underground Catholic Church.

According to Chambon, the first women religious in China were consecrated virgins or “beatas” in the 1600s. These women made private vows, lived with their parents and assisted the priests with religious education, baptizing when the priest was absent and leading parish prayer life. They reminded me of Angela Merici, the Italian foundress of the Ursulines in 1535. She and her sisters lived similarly to Chinese beatas and had no required conventual life or uniforms, nor were they referred to as “Sister.” These women were an anomaly in a culture with few Catholics and where women were expected to marry and be mothers.

Sr. Joyce Meyer poses with members of a congregation known as St. Joseph Sisters during a 2003 trip to China when she was executive director of the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters. The congregation was founded in 1872 by a bishop, was suppressed under Mao Zedong, then was re-founded in 1981. (Courtesy of Joyce Meyer.)

Beatas continue this ancient form of religious life in China today, with mostly elderly and a few young women. At times, according to Chinese sisters I’ve spoken with, there has been pressure from the Vatican to conform to traditional Western communal religious life, even though canonically, a similar form does exist, such as consecrated virgins.

Chambon described the beata life as diaconal, meaning service to a local, usually rural, church in contrast to women who live in community and may be sent to various regions of a country or beyond. Some continue to live in their family homes, and others might live and work in the parish house with the priest. In this case, they are usually assigned by the bishop for a five-year period to protect them from undue attachment. Formation, according to Chambon, was originally individual mentoring by elder beatas, but later as more women were attracted, formalized education and formation in groups evolved.

When Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and communism took hold in the 1950s, religion was technically allowed, but public practice was frowned on. As religious social, health and education institutions were taken over by the government, religious congregations began dispersing. They feared what could happen to them, as many religious people were being killed and imprisoned. Expatriate religious left the country and Chinese women returned home to live with their families, reverting to life similar to that of beatas. These women kept the church alive, in secret, as priests were killed or imprisoned.

Sr. Joyce Meyer met a Franciscan sister, then age 90, who re-founded the group in 1985 after it had been suppressed. This photo was taken during a 2003 trip to China when Meyer was executive director of the Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters. (Courtesy of Joyce Meyer.)

After Mao’s death in 1976, public practice of religion was once again allowed. Nuns who had been in hiding began to reclaim their public religious life and revive groups founded before the revolution. Recruitment was strengthened in the 1990s, as was a re-shaping to a more communal life. New recruits, belonging to revived local religious groups, were given opportunities either by their own or other international congregations or sisters or priests to study in the United States and elsewhere. As the women returned, these newly educated sisters began to find their own “national voice,” and it was different from the West; not all they had learned fit life in China. However, as they brought new ways of thinking and doing things, not unexpectedly, tensions increased in relationships with priests and bishops who had not had the opportunity to study abroad.

Nevertheless, the nuns remain deeply engaged in parish and diocesan work, as the majority belong to diocesan-founded groups. They are considered diocesan servants, caring for children, people with disabilities and elderly people in the local church community. Their works are eclectic, at times requested by the government. A few groups have initiated their own ministries to the most marginalized, but these must be approved by the country’s religious affairs office.

Only a small percentage percent of the sisters’ time is spent in evangelization, according to Chambon. They are often caught between their political local contexts and the voice of the Vatican, which does not always understand the complexity of relationships of government and local church authority that they must navigate. They are questioned about their “works” and their “spiritualities” that are sometimes not seen as “fitting” into canonical categories, according to Chambon, the survey and conversations I’ve had with Chinese sisters.

They also struggle to survive economically, frequently receiving little or no compensation for their services, often left “faceless, nameless and voiceless,” Chambon said. This is true, even though as Chinese nationals, they hold a recognized place in the society, both by the government and the people of God. How can this be? How can commitment to the local church as companion servants with the priests or bishops who “together are (considered) the face of God,” he said, and as women who kept the church alive during the dangers of the revolution, go unrecognized monetarily?

The beata and missionary forms of religious life are also evolving. Younger members of both forms long for a more contemplative dimension to their religious commitment. Currently there are no specifically contemplative congregations in China to assist them, so these younger women want to shape their lives of service with more time for contemplative prayer and to assist their local lay communities to develop deeper prayer lives.

As I listened to Chambon and read his paper, I was greatly amazed by these women’s historic and resilient commitment to Gospel life and their ability to thrive in the midst of much uncertainty. They must constantly find their balance between an “unpredictable Chinese state or an authoritarian bishop,” who could at any moment disengage them from a kindergarten or elderly home where they have been serving, he said. In spite of their many challenges and vulnerabilities, it is clear to me that women religious have been and are essential to the future of the Catholic Church in China.

[Sister Joyce Meyer is a member of the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. She is on the boards of the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, Medicines for Humanity and the International Foundation of the Good Shepherd Sisters and has served as international liaison to women religious for Global Sisters Report since January 2014.]